Lesson Objective: Learning the fundamentals of selling calls

When to sell calls: Generally, when you expect the stock to trade close to or move below the strike price you select.

Now, that we have learned the key concepts of buying options, let’s look at selling them. In essence, this is just taking the opposite sides and views of buying options. However, the first and foremost difference with buying options lies in the fact that writers of options have actually no choice, they only have obligations; just like an insurance company will not have the choice to indemnify you or not (if your claim has merit): it will have the obligation to comply with the terms of the contract and make you whole.

When you sell a call, you sell an option to buy 100 shares of (1) a stock of your choice at (2) a strike price of your choice (3) before an expiration date of your choice. As the option seller (or “writer”), you are said to be “short” the call. Just be aware that the term “option to buy” in the example above refers to the other party (i.e., the buyer), not you the seller: in other words, the other party has the option to buy from you, and you have the obligation to sell to the other party in case s/he exercises her/his option at or before the expiration date.

So, by selling a call, you promise the other party (the buyer of the call) that you will sell him/her the stock at the agreed-upon price (the strike) even if the stock price is higher. In other words, you are providing a guarantee, insurance, or protection to the other party against an increase of the stock price above the strike price.

Given the risk taken by the seller of the option and its obligation to comply, s/he must be compensated and consequently will receive the option premium upfront.

Let’s take an example: You sell XYZ 21 Jun 2019 $100 Call for $2. What does that mean?

It means that you sell (i.e., you are short) an option to buy 100 shares of XYZ at the $100 strike before the 21 of June 2019. For your trouble, you are compensated $2 per share now (i.e., you receive a total credit of $200).

If the stock price goes above $100 at expiration, the buyer will exercise his/her option and as the seller, you will be “assigned” the stock, which means that you will have the obligation to sell the stock at $100 to the buyer.

- If you already have the stock in your portfolio then your sale is covered by the existence of the stock, and therefore you are said to have sold a “covered call” in this case. We will devote a whole lesson to covered calls in a later module.

- However, if you don’t have the stock in your portfolio, you are said to sell a “naked” call, which your broker might prevent you from doing altogether depending on your profile, financial situation, and overall expertise with options. If allowed, your broker will lend you the stock to be sold to the option buyer until you actually buy the stock yourself from the market at a later time to pay your broker back.

In the present case, we assume that you are selling a naked call.

So, you are hoping that the stock will stay under $100. You sell a naked call if you are bearish on XYZ.

Indeed, a short call expires worthless when the stock price is below the strike at expiration: any rational person could and would buy the exact same stock at a cheaper price from the market rather than at the strike (and higher) price from you.

If the option expires worthless, you get to keep the premium and your capital remains free and can be used for another similar trade or one with a different strategy.

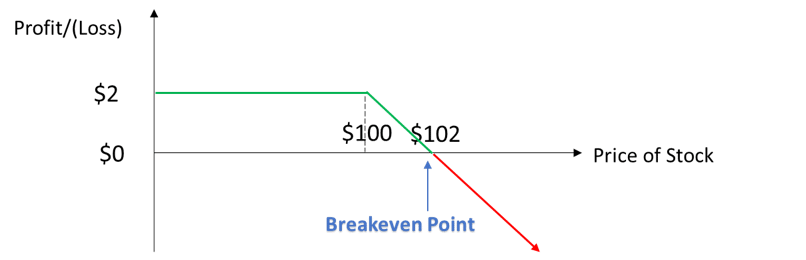

Look at the payoff diagram below:

As you can see above, if the stock is below $102 (strike + premium received) at expiration, you make money (the section of the graph in green). At $102, you breakeven, while you lose money if the stock ends above $102 (the section of the graph in red). So, you can make money even if the stock price ends slightly above the strike, provided that it stays below the breakeven point.

Your maximum gain is capped at $2 (per share) – the premium you received – when the stock ends below $100 at expiration.

However, your maximum loss is theoretically infinite: you may be obligated to sell the stock to the option buyer at the lower strike price by buying the stock from the open market at a much higher market price if it gapped up suddenly and significantly due to an exceptional event (like a much-better-than-expected earnings report, or favorable regulatory ruling, etc.).

So, your immediate question might be right: why would I ever enter such a trade where my gains are limited but not my losses?

To collect a premium and get paid upfront! Also, you do not have to be 100% right on the direction of the stock to be profitable, contrary to buying options.

In addition, as the seller of the option, time works to your advantage. Recall what we discussed in the previous lessons on buying options: as time goes by, the value of options goes down, all else being equal. So, the owner (buyer) of the option sees the value of the option s/he holds decrease until expiration while the seller sees it increase (since s/he stands opposite to the buyer).

Let’s sum up what we have learned so far:

| Outlook on Stock | Premium | Loss Zone and Maximum Loss | Breakeven | Gain Zone and Maximum Gain | Requirements to be Profitable | |

| Selling a Call

|

Bearish or expect stock to trade close to strike | You receive the Premium | Stock Price > Strike + Premium received

Max loss unlimited |

Stock Price = Strike + Premium received | Stock Price < Strike + Premium received

If Stock Price < Strike => option ends worthless Max gain limited to premium received (Stock Price < Strike) |

Generally speaking, you must be right on the direction of the stock, however you could be slightly wrong provided that it is by a margin narrower than the premium received. |